The Daffodils of Beguinage

From the hubbub of a pre-pandemic Bruges, a small cobblestone bridge over a canal and an arched gateway led me into a long-forgotten world of women. The lush green central square had retained specks of yellow from a spring bloom of daffodils, much like the glimmer of its free-spirited past occupants. The young poplars that stood sentry by their erstwhile white houses had not witnessed those revolutionary days of the 13th century.

Bruges, in the Flanders region of Belgium, was more than waffles and pretty canals. Underneath its surface, breathed one of the earliest women’s movements, as it did in Antwerp and Ghent.

Feminisme, coined much later in 19th century France, is not to be confused with this movement.

Ten Wijngaerde, where I stood, is one of the architectural units built by these groups of individualistic women called Beguines. Governed by women, for women, their communities called Begijnhof or Beguinages were home to women who heeded their call to lead an independent life and chose not to be bound by any vows, marital or religious.

WHO WERE THE BEGUINES?

Women had been trying to break the shackles of patriarchal control from 800 years before modern times. Beguines were women who did not conform to societal rules during an age when they were far less free-willed than their current counterparts.

Throughout the middle ages, independent and spiritual women from different walks of life desired to live a life that was neither dependent on a man nor separated from society through monastic vows. These women prompted a movement that built dedicated communities across Belgium and the Netherlands, which further spread to France, Germany, and Luxembourg.

By and large, Beguines were heretics whose mysticism was different from the religious inclinations of a nun. But they were not the sole residents of the Beguinages.

Single women from all social classes were welcome to live in these communities, which further set these establishments apart from a nunnery or convent. Their marital status was insignificant. Unmarried and widowed women lived there, and so did formerly married ones separated from their spouses.

To move to a Beguinage and call it home did not require them to commit themselves to the place for a lifetime. Unbound, they could choose to leave any time they wanted - to get married or for reasons of their own.

Although the beguines were not secular, their idiosyncrasies intrigued this atheist woman of the 21st-century. They upheld their self-regard by being in control of their lives on their terms. Even in devotion, they were liberal, formed their exclusive norms and values, and followed democracy to elect a Grootjuffrouw (or Grand Mistress) as their leader. They had achieved - even if for a limited time - the elusive freedom of choice.

STEREOTYPE VS REALITY

As a society, we rely on each other to survive, but the stereotypical image of the codependent is shoved more often upon women than men. Invalidating this unjustified popular belief, these women proved their potential to both sustain themselves and support others around them.

The Beguines worked to earn a living – as teachers in schools, nurses in infirmaries, lacemakers in the textile industry, and even writers with revolutionary opinions. Those without skills rented out properties that they owned as a way of sustenance.

The Beguinages encouraged them to be self-reliant and also aid their community through contributions from their income. Outside of their community walls, these women tended to the poor and the sick, finding spirituality in their dedication to charitable works.

It is difficult to imagine how the Beguines evaded the control of the Church or getting married against their will when many women struggle with their much-deserved personal independence and choice to this day. But they did, for hundreds of years, until supercilious dominance started wiping them out.

WHY WERE THEY PERSECUTED?

Societal changes are often stealthy. During the initial days (read decades) of the Beguine movement, their life within the Beguinage walls did not bother the authoritative people living outside of it. How could a few isolated groups of women jeopardize their power?

But the growing economic power of the Beguines, their independence from the Church and other authorities, and their zeal to express their views through their writing started attracting repudiations and denunciations. Their freedom of movement drew flak as the character of unescorted wandering women was considered questionable. Their philanthropy, liberal attitude, and feminine solidarity caused a simultaneous increase in their popularity, inciting insecurity in their opposition. These factors aroused distrust in their antithesis and proved to be detrimental for these free-spirited women.

The Beguines’ flair for business soon started threatening the town merchants as they struggled to bring them under the economic control of the male-run guilds. In particular, their work in the textile industry irked the cloth unions that wanted to reserve the privileges for themselves.

The church and conservative section of the public grew suspicious of this independent and informal group of women they could not control. They accused the beguines of heresy - for their refusal to take vows, forming their separate practices of worship, and attempting to impart spiritual guidance to the community outside their walls.

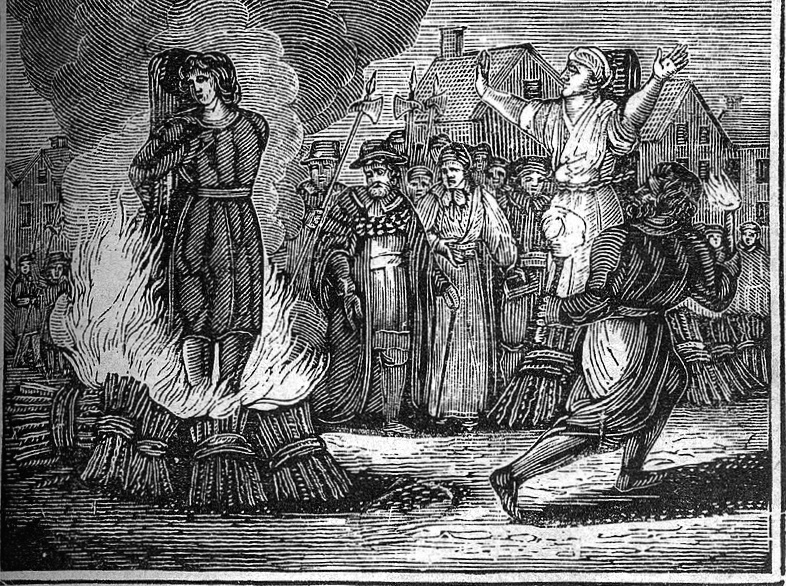

Several Beguines wrote and published their works of mysticism, which differed from traditional religious beliefs. Authors and poets like Mechthild of Magdeburg, Hadewijch, and Marguerite Porete faced immense opposition for expressing their ideas. The circulations of their books were banned; public squares became venues for book burning targeting published copies.

The intolerance soon took a heightened form when Porete, the author of The Mirror of Simple Souls, refused to remove her book from circulation or withdraw her views. She was burnt at stake on account of heresy on 1 June 1310.

Punishments for holding anti-dogmatic opinions have persisted through the centuries, the level of which depends on the amount of barbarism the living generations can tolerate or disregard.

The Beguines faced persecution for desiring to be unrestrained, which was - and in certain parts of the world still is - an unfavorable lifestyle for women. The noose had started to tighten around their necks.

THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL

Early 14th century, following interfering investigations by church authorities, the independence of the Béguinages began to dwindle. The ecclesiastical authorities, who were clamping down on every voice of dissent, disbanded the Beguine movement during the Council of Vienne in 1311.

While the smaller communities perished, the Church overtook control over big ones like Ten Wijngaerde of Brugge. They were assigned priests as presiding authorities. To survive, the Beguines had to modify their way of life, adhering to nun-like dress codes and taking compulsory vows of chastity. Even their freedom to leave the community became rigid, unlike their heydays.

Turbulent times followed as both the Great Famine of 1315-1317 and the Black Death, the deadliest pandemic of our world, ravaged Europe one after the other. Although the Beguines continued caring for the poor and nursed the sick during the Plague, they were closing in on their breaking point. The crisis of the late Middle Ages assisted the existing intolerance against them.

The beguines disappeared, but the beguinages remained - a reminder of their outstanding legacy. In 1998, Ten Wijngaerde, along with 12 other Flemish Beguinages, was listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Along with their architectural significance, UNESCO recognizes the cultural contributions of this generation of women who sought to lead a life of far greater independence than that permitted to women and built a social unit that respected the individuality of its members, along with their spiritual and materialist needs. Their heritage is worthy of such veneration.

BACK IN BRUGES

The small pedestrian access fitted on the entrance gate of Ten Wijngaerde was not overwhelmed on that spring afternoon. The crowds of tourists were elsewhere, indulging in other obvious delights this Belgian city had to offer.

Patches of ivy adorned its wall, creeping down towards the canal, trying to touch its water. On the opposite bank, swans and ducks chose to take an undisturbed afternoon nap across its weathered red brick façade, on the grassy square called Wijngaardplein.

Although some Beguines raised their voices when pushed to the brink, historical records do not portray them as rebellious. All they wanted was to live a peaceful life in these tranquil havens they built before the prejudices and insecurities of others crushed them to oblivion.

To this day, the plights of single women are no different. The progressive section of society I belong to time and again issues me subtle reminders of my supposed incapability of sustaining life without a man. Climbing mountains, diving to the depths of the ocean, and traveling around the world without assistance were not enough to prove my survival skills. Neither is my earning capability nor my kitchen prowess enough to validate my self-sufficiency. Women are gaslit to perceive a weakness within them and pushed to choose a symbolic savior rather than a companion. In a world where homemakers, who sustain an entire family, are considered dependent, the equal companionship and camaraderie between men and women still seem a Herculean vision.

Eight centuries later, I could still feel a sense of serenity emanating from the Beguinage of Bruges - a place where freedom and individuality reigned. Under the poplars, careful not to trample the remnants of the daffodils, one can slow down to introspect their life choices and their accessibility to those in silence. I am capable of asserting my freedom of choice for the time being; has every woman been so fortunate?